Combinatorial Optimization of Antibody Libraries via Constrained Integer Programming

Published:

In this blog post, we present ProtLib‑Designer (PLD), a novel method for designing diverse and high-quality antibody libraries through combinatorial optimization. PLD leverages AI-based in silico deep mutational scanning to evaluate the effects of mutations on antibody properties, and formulates library design as a constrained integer linear programming (ILP) problem. By explicitly optimizing for multiple objectives—binding affinity, developability, and diversity—PLD generates antibody libraries that outperform traditional greedy and evolutionary approaches. We will explore the key components of ProtLib‑Designer, its optimization framework, and empirical results demonstrating its effectiveness in generating superior antibody libraries.

📄 Read the paper: biorxiv.org/2024.11.03.621763v3

💻 Browse the code: github.com/LLNL/protlib-designer

Introduction and Motivation

Antibodies are one of the fastest-growing classes of therapeutics, with major impacts in treating cancer, autoimmune diseases, and other conditions. Developing new antibody drugs often begins with directed evolution, where large mutant libraries are experimentally screened to find candidates with desirable properties. A key challenge in antibody library design is balancing multiple objectives:

- Binding affinity: Mutants should bind the target antigen tightly for efficacy.

- Developability: Mutants need favorable properties (stability, solubility, etc.) for manufacturing and safety.

- Diversity: The library should cover a broad sequence space, increasing the chance of finding a successful lead and avoiding predictive biases.

Traditional approaches for initial library generation (e.g. random mutagenesis guided by deep mutational scanning or molecular simulations) can enrich for high-affinity antibodies, but they often require extensive data or computation and may overlook diversity. Deep mutational scanning (DMS), for example, exhaustively measures the effect of every possible amino acid mutation on protein function in a high-throughput assay. While DMS data can highlight beneficial mutations, designing a whole library involves combinatorial optimization to select a set of mutants that jointly maximize affinity and developability while remaining diverse.

Recent advances in deep learning offer powerful in silico tools for protein engineering. By leveraging models trained on massive sequence and structure datasets, we can predict the intrinsic effects of mutations (e.g. how likely a mutation is to produce a stable, “natural-like” antibody sequence) and extrinsic effects (e.g. how a mutation affects binding to a specific antigen). ProtLib‑Designer (PLD) is a new method that harnesses these models and formulates library design as a constrained optimization problem. The approach targets a cold-start scenario – designing an initial diverse library without any experimental fitness data – which is crucial for rapid response to emerging targets or escape mutants.

ProtLib‑Designer Overview

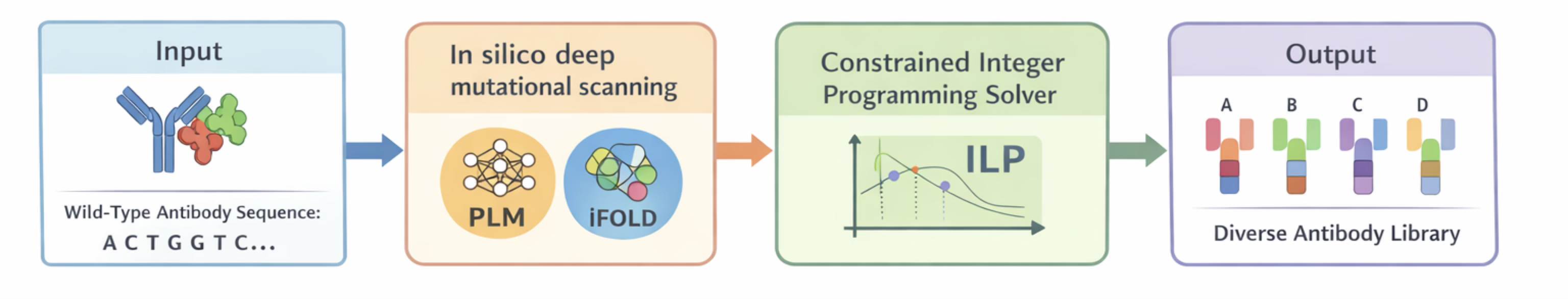

ProtLib‑Designer combines AI-Guided mutational fitness profiling with constrained integer programming to generate high-quality antibody libraries. In simple terms, it performs the following steps:

AI-Guided Mutational Fitness Profiling: Given a target antibody (and its antigen complex), ProtLib‑Designer virtually “scans” all allowed mutations using AI models. A protein language model (PLM) assesses each mutation in the context of the antibody sequence (intrinsic fitness), and an inverse folding model evaluates each mutation in the context of the 3D antibody-antigen structure (extrinsic fitness related to binding). This yields a score or “fitness cost” for every single-point mutation at each position.

Combinatorial Optimization: Using these scores, the method then selects an optimal set of mutants (whole sequences) to form a library. This is posed as an integer linear programming (ILP) problem: maximize overall predicted fitness of the batch while satisfying diversity constraints. The ILP ensures each chosen sequence has a limited number of mutations and that the library isn’t dominated by repetitive or highly similar mutants.

Solve-and-Remove Strategy: To enforce diversity, ProtLib‑Designer employs an iterative “solve-and-remove” algorithm. It repeatedly finds the best-scoring sequence under the current constraints, then removes (rules out) not only that sequence but also any other candidates too similar to it (within a defined Hamming-distance or sequence similarity radius). By eliminating clusters of redundant solutions after each selection, subsequent ILP optimizations explore new regions of sequence space, yielding a diverse set of top performers.

Optimized Library Output: The final result is a library of $K$ antibody sequences that are co-optimized for binding and developability scores, and explicitly diverse. This library can then be synthesized and tested, serving as a strong starting point for experimental screening or further affinity maturation.

Schematic overview of the ProtLib‑Designer pipeline for antibody library design. (a) A wild-type antibody sequence (in complex with its antigen) provides the structural and sequence context. Key residue positions (e.g. in complementarity-determining regions) are identified for mutation. (b) In silico deep mutational scanning is performed: for each position, every possible amino acid substitution is evaluated using a sequence-based model (protein language model) and a structure-based model (masked inverse folding) to predict the mutation’s effect on intrinsic stability/learnability and extrinsic antigen binding. (c) The predicted mutational effects feed into a multi-objective ILP solver which selects an optimal set of mutants. The ILP encodes multiple objectives (maximize predicted binding affinity, maximize developability proxy, etc.) and diversity constraints that limit repeated mutations. (d) Using an iterative solve-and-remove strategy, the solver produces a library of $K$ antibody variants that balance high predicted fitness with broad diversity.

AI-Guided Mutational Fitness Profiling

To evaluate mutations in silico, ProtLib‑Designer leverages two complementary deep learning models without requiring any lab measurements:

Protein Language Model (PLM): A transformer-based language model (such as ProtBERT or ProtGPT) that has learned statistical patterns of natural protein sequences. It provides a sequence-level fitness proxy – often mutations that make an antibody sequence less “natural” (lower probability under the model) correlate with reduced stability or expression (poor developability). For each candidate mutation, the PLM assigns a score $s^{\text{PLM}}$ based on how probable the mutated residue is in the context of the rest of the sequence. We can define this intrinsic score as a log likelihood ratio comparing the mutant vs. wild-type residue at position $i$:

\[s_{i\to a}^{\text{PLM}} \;=\; -\log P_{\text{PLM}}\big(X_i = a \mid X_{-i} = w_{-i}\big) \;+\; \log P_{\text{PLM}}\big(X_i = w_i \mid X_{-i} = w_{-i}\big) \,.\]Here $w$ denotes the wild-type antibody sequence, $w_i$ is the original amino acid at position $i$, and $a$ is a candidate mutant amino acid. Intuitively, $s_{i\to a}^{PLM}$ will be low (good) if the mutation is plausible or conservative according to the sequence model, and high if the mutation is evolutionary unlikely (potentially destabilizing).

Structure-Based Inverse Folding Model: To estimate binding affinity changes (extrinsic fitness), ProtLib‑Designer uses an antibody-specific inverse folding model (e.g. AntiFold, a variant of ESM-IF1 fine-tuned for antibody-antigen complexes). This model predicts how well a given antibody sequence fits or “folds” with the antigen structure. Similarly, a score $s^{\text{IF}}_{i\to a}$ is computed as a log-ratio of the mutant vs. wild-type probability according to the inverse folding model (including the antigen context). A low value of $s^{IF}$ suggests the mutation likely maintains or improves binding to the antigen, whereas a high value indicates a disruptive mutation.

For each position $i$ in a predefined set of mutable sites (e.g. residues in CDR loops or antibody interface), we compute $s_{i\to a}^{\text{PLM}}$ and $s_{i\to a}^{\text{IF}}$ for all 19 possible amino acid substitutions (excluding the wild-type residue). These scores serve as a surrogate mutational fitness landscape for the antibody: lower scores are better. Crucially, this scoring is done in silico, combining general sequence knowledge with structure-specific context – no experimental data needed. Such zero-shot predictors have shown promise in identifying beneficial mutations in antibodies.

ILP Formulation for Library Design

Given the mutational scores, ProtLib‑Designer faces a combinatorial optimization problem: select a batch $B = {x_1, x_2, \dots, x_K}$ of $K$ mutant sequences (each differing from the wild type at a small number of positions) that jointly minimize the predicted objective scores while satisfying diversity requirements. This can be framed as a constrained multi-objective optimization:

\[\min_{B} \; \; F_{\text{pred}}(B) \;=\; \Big(F_{\text{binding}}(B),\; F_{\text{developability}}(B)\Big) \,, \quad \text{s.t.} \;\; \text{diversity}(B) \;\ge \; \delta\]where $F(B)$ is a vector of aggregated model-based scores for the batch (e.g. predicted binding affinity and developability), and $\delta$ is a minimum diversity.

In practice, ProtLib‑Designer combines the PLM and inverse folding scores into a single additive objective for each sequence (a weighted sum or linear combination), and optimizes this single scalar objective, but it evaluates results on multiple criteria. The ILP (integer linear program) is defined over binary decision variables that represent which mutations occur in which sequences.

Optimization constraints: The ILP includes various constraints to ensure feasible, diverse libraries:

- Mutation count per sequence: Each designed antibody $x \in B$ is constrained to have between $N_{\min}$ and $N_{\max}$ mutations relative to the wild type (e.g. between 5 and 8 amino acid changes). This keeps individual mutants reasonably similar to the starting antibody, increasing the chance they retain overall fold and function.

- Per-position mutation limits: To maintain diversity across the library, ProtLib‑Designer limits how frequently any particular mutation is used. For example, for each position $i$ and amino acid $a$, we can impose: \(\sum_{x \in B} \mathbf{1}[x_i = a] \;\le\; \Delta_1, \quad \forall i,\; \forall a \neq w_i\,,\) meaning at most $\Delta_1$ of the $K$ sequences can share the same mutation (position $i$ mutated to $a$). If $\Delta_1 = 1$, no mutation is repeated in more than one sequence; larger $\Delta_1$ allow limited repetition but prevent any single mutant substitution from dominating the whole batch.

- Position usage spread: Likewise, we can ensure no single position is mutated in too many sequences. For each position $i$ (among the $N$ mutable sites): \(\sum_{x \in B} \mathbf{1}[x_i \neq w_i] \;\le\; \Delta_2, \quad \forall i\,,\) which caps how many sequences carry any mutation at position $i$. This prevents the library from, say, mutating the same hot-spot position in every sequence while leaving other positions unchanged. By tuning $\Delta_2$, we encourage a broad exploration of different positions across the library.

- Uniqueness: The formulation inherently avoids duplicate sequences. Each sequence design is a combination of mutation decisions, and the ILP (or iterative selection process) is set up such that $x_p = x_q$ (identical sequences) cannot occur for $p \neq q$.

The solve-and-remove algorithm ensures these diversity constraints are met even when generating very large libraries. Rather than solving a single huge optimization for all $K$ sequences, ProtLib‑Designer adopts a greedy iterative approach:

- Solve the ILP (or a simplified version) to find the single best mutant sequence $x^*$ given the current remaining mutation options.

- Add $x^*$ to the library $B$.

- Remove $x^*$ and its neighbors from the search space.

- Repeat the ILP solve for the next sequence, under the updated constraints, until $K$ sequences are selected.

This iterative diversification strategy is illustrated by an animation of the solution space being carved out step by step (where each iteration picks a high-performing sequence and excludes a “ball” of radius $\epsilon$ around it in sequence space).

Illustration of the solve-and-remove strategy in ProtLib‑Designer. At each iteration, the best-scoring mutant sequence is selected (star), and a neighborhood of similar sequences (shaded area) is removed from consideration in subsequent iterations. This process continues until the desired library size is reached, ensuring diversity among selected mutants.

Through this combination of explicit constraints and iterative solution removal, PLD achieves a diverse portfolio of antibody designs without sacrificing predicted performance. Notably, the ILP framework provides a transparent way to trade off objectives by adjusting weights or constraints, and it guarantees the constraints (like diversity metrics) are satisfied by construction. This stands in contrast to evolutionary algorithms, which must implicitly maintain diversity in their population. In fact, one of the baselines we compare against is SPEA2 – the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm 2 – a multi-objective genetic algorithm that uses Pareto dominance counts for convergence and density estimation for diversity maintenance. Such evolutionary methods stochastically explore trade-offs, whereas ProtLib‑Designer directly optimizes them with problem-specific constraints.

Experimental Results and Benchmarks

We evaluated ProtLib‑Designer on three antibody case studies: Trastuzumab, D44.1, and Spesolimab. These antibodies vary in their target and sequence properties – Trastuzumab is a well-known anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody (with 10 mutable positions considered in its heavy chain), D44.1 is an antibody against hen egg lysozyme (34 mutable positions across heavy/light chains), and Spesolimab targets the IL-36 receptor (47 mutable positions). In each case, a library of $K=1000$ mutants was designed using PLD under the same mutation number limits ($5 \leq \text{mutations per sequence} \leq 8$).

Baselines: ProtLib‑Designer (with diversity enforcement) was compared to several baseline algorithms:

- LMG (Linear Mutant Generator): a greedy strategy that sequentially adds the globally best mutations to each sequence without explicit diversity optimization. This method, akin to earlier ILP approaches without diversity constraints, tends to produce libraries with many similar high-scoring mutants.

- MODIFY: a recently published machine-learning guided library design method that optimizes for improved fitness and some diversity heuristics (based on Ding et al. 2024).

- SPEA2 (Evolutionary algorithm): a classic multi-objective genetic algorithm optimizing the two objectives (predicted binding vs developability) simultaneously. SPEA2 maintains a population of solutions and seeks a Pareto-optimal front of trade-offs. It inherently aims for diverse solutions, though not with hard guarantees.

- Multi-Objective GFlowNet: Additional baselines like a multi-objective GFlowNet were also considered in the appendix, but we focus on the main comparisons here.

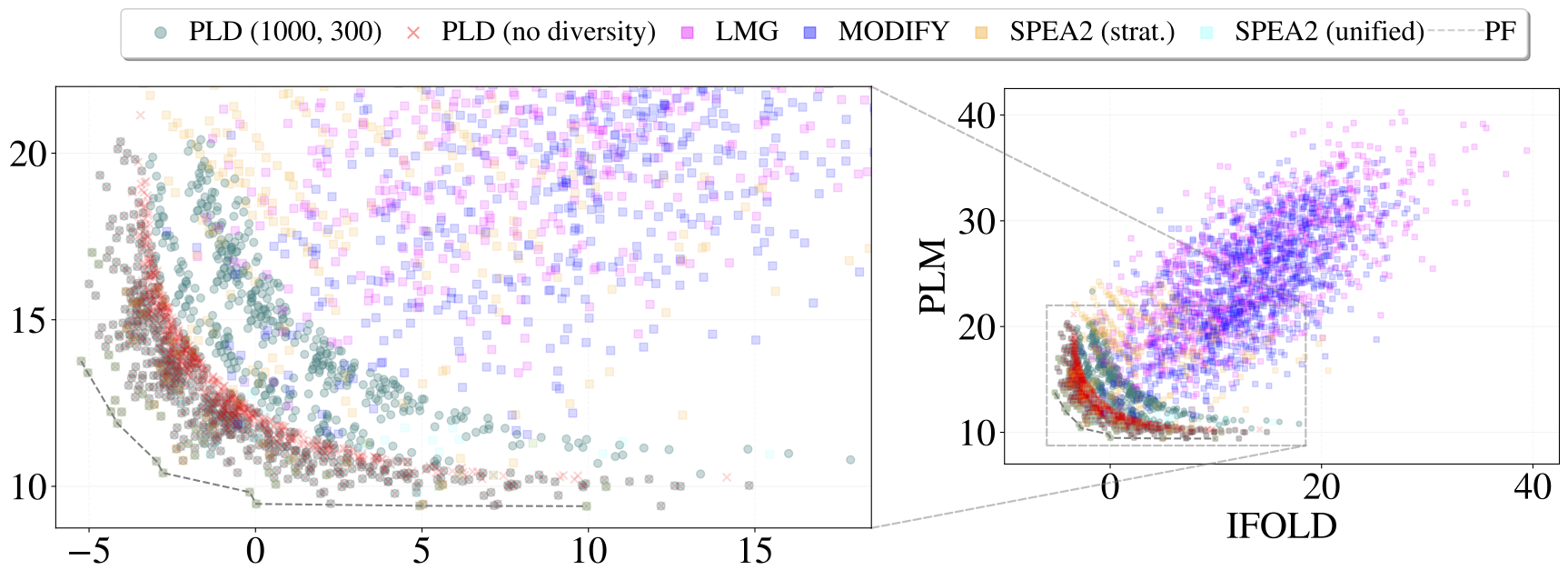

Objective values of mutants generated by ProtLib‑Designer (PLD) and baseline methods for Trastuzumab in complex with the HER2 receptor. Each point represents a 5 to 8-point mutant. The zoomed-in perspective focuses on the objective values of the Pareto front and mutants generated by PLD with, and without, diversity constraints.

Key Metrics: To quantitatively evaluate library quality, the paper reports:

- BEU (Batch Expected Utility): a metric that integrates the performance of the entire batch over a range of utility trade-offs. Intuitively, a lower BEU means the library as a whole covers better objective values across different weightings of the goals. PLD achieved the lowest (best) BEU, indicating its mutants collectively minimize the objectives more effectively than baselines.

- Hypervolume (HV): the hypervolume indicator measures the volume of the objective space dominated by the Pareto front of the solutions. In multi-objective optimization, hypervolume is a strict Pareto-compliant measure of front quality – higher HV means the set of solutions reaches better and more diverse trade-offs. ProtLib‑Designer obtained the highest hypervolume in all cases, matching or exceeding the Pareto front achieved by SPEA2 and outperforming other methods. In fact, PLD was able to recover a Pareto front as good as the true combined Pareto front of all methods, especially for the smaller Trastuzumab problem.

- Diversity metrics: including sequence entropy (how evenly mutations are distributed) and the number of unique sequences. By design, PLD always produces the full 1000 unique sequences, whereas methods like SPEA2 struggled – for D44.1, a standard SPEA2 run yielded ~26% fewer unique sequences than requested due to converging populations on similar individuals. (We had to run multiple SPEA2 instances with stratified mutation counts to populate 1000 solutions for Spesolimab.) PLD’s libraries had high per-position entropy (e.g. >3 bits) indicating a wide spread of different mutations.

- External evaluation: To validate that PLD’s solutions are not only good according to the ML model scores but also in realistic terms, we checked “humanness” and predicted binding of the libraries. They used ProtGPT2 (a generative model) to score sequences’ likelihood (a proxy for how human-like or developable they are), and a separate ML classifier, trained on experimental binding data, to predict how many sequences would bind the antigen (oracle fitness).

| Method | # of unique sequences ↑ | Residue entropy ↑ | BEU ↓ | HV ↑ | Average humanness ↑ | Oracle fitness (%) ↑ | Avg. rank ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLD (1000, 300) | 1000 | 3.22 | 4.615 | 2231.90 | -1296.73 | 58.2 | 2.50 |

| PLD (no diversity) | 1000 | 3.11 | 4.30 | 2231.90 | -1293.68 | 61.8 | 2.17 |

| LMG | 1000 | 4.75 | 10.70 | 1937.70 | -1309.75 | 17.1 | 4.33 |

| MODIFY | 1000 | 3.97 | 10.14 | 2012.43 | -1308.27 | 18.6 | 3.83 |

| SPEA2 (strat.) | 263 | 2.74 | 6.24 | 2231.90 | -1290.01 | 38.02 | 3.50 |

| SPEA2 (unified) | 69 | 2.60 | 4.08 | 2231.90 | -1282.57 | 68.12 | 2.67 |

| GFlowNet | 1000 | 4.99 | 12.42 | 1681.66 | -1779.05 | 12.4 | 5.83 |

Table: Diversity and fitness metrics of libraries generated by each algorithm for Trastuzumab. Columns: # of unique sequences (library size), Residue entropy (diversity measure), BEU (Batch Expected Utility, lower is better), HV (hypervolume, higher is better), Average humanness (how human-like sequences are, higher is better), Oracle fitness (%) (highest fitness achieved, higher is better), Avg. rank (average rank across objectives, lower is better). Bold values indicate the best performance and italicized values the worst in each column.

PLD’s library showed a ~3.5× higher fraction of predicted binders (oracle fitness) than the greedy LMG and MODIFY libraries, while also having higher average humanness. In other words, PLD didn’t sacrifice developability for affinity – it improved both simultaneously. In visualizing results, PLD’s mutant libraries tend to cluster near the Pareto-optimal frontier of the two objectives, often forming “stratified layers” when diversity constraints are active. This layering reflects how PLD systematically trades off a slight increase in one objective for a gain in diversity. By contrast, the greedy and MODIFY baselines produce a scatter of solutions (described as a “shotgun” pattern) that are not as Pareto-efficient. SPEA2 solutions lie closer to the front but had gaps due to missing unique sequences.

Overall, ProtLib‑Designer outperformed the baseline approaches, delivering libraries with superior multi-objective scores and guaranteed diversity. For example, in the Trastuzumab case, PLD achieved the highest hypervolume (on par with the theoretical Pareto optimum) and best average rank across all metrics. Its sequences were more likely to be functional (by proxy metrics) than those from other methods. These results demonstrate that incorporating constrained optimization with accurate in silico scoring yields a powerful pipeline for antibody engineering.

Conclusion

ProtLib‑Designer represents a significant advancement in computational antibody library design by jointly optimizing for affinity, developability, and diversity from the outset.

Key features and implications of this work include:

- Multi-objective optimization with explicit diversity: By formulating library design as an ILP with diversity constraints, PLD ensures a broad exploration of sequence space without relying on random diversity maintenance. This leads to libraries that cover many viable solutions and avoid the pitfalls of overly greedy selection.

- Integration of sequence and structure models: The use of both PLM and inverse folding scores means the designed mutants are predicted to bind well and remain realistic antibodies. This dual scoring addresses the common trade-off in protein engineering between functionality and developability.

- Efficiency in cold-start scenarios: Without needing any prior experimental data, PLD can generate high-quality mutant libraries in silico. This is valuable for rapid response situations (e.g. developing antibodies against a new pathogen or escape mutant). It essentially jump-starts the directed evolution process with a smarter initial pool, potentially reducing the rounds of wet lab screening needed.

- Strong empirical performance: In head-to-head comparisons, ProtLib‑Designer’s libraries showed better coverage of the Pareto front (higher hypervolume) and yielded more predicted binders than libraries from greedy or purely ML-guided methods. It matched the prowess of an evolutionary algorithm (SPEA2) in finding optimal trade-offs, while also fulfilling practical library size requirements that SPEA2 struggled with.

In summary, ProtLib‑Designer demonstrates how constrained combinatorial optimization can be coupled with state-of-the-art predictive models to tackle the complex design landscape of antibodies. By simultaneously accounting for affinity, developability, and diversity, it produces candidate libraries that are both high-quality and robust. This approach could help researchers more quickly discover therapeutic antibodies or generate focused libraries for downstream optimization.

Moving forward, the framework is flexible enough to incorporate additional objectives (e.g. immunogenicity or specificity scores) and could be extended with improved models as they become available, making it a promising platform for machine learning-driven protein engineering.